Select a site alphabetically from the choices shown in the box below. Alternatively, browse sculptural examples using the Forward/Back buttons.

Chapters for this volume, along with copies of original in-text images, are available here.

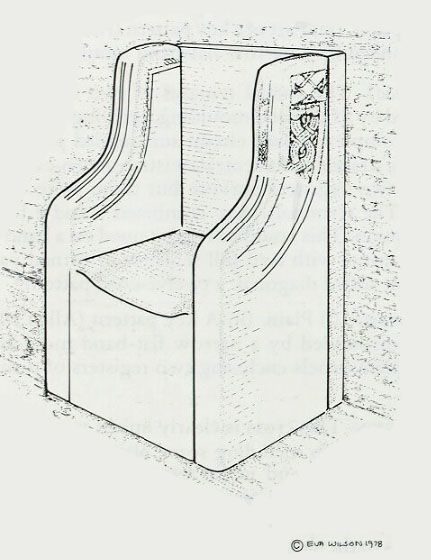

Object type: Arm of chair

Measurements: H. 49 cm (19.25 in); W. (top) 25.5 cm (10 in), (centre) 28 cm (11 in); D. 12.5 cm (5 in)

Stone type: Medium-grained, massive yellow sandstone

Plate numbers in printed volume: Fig. 18; Pl. 158.812-817

Corpus volume reference: Vol 1 p. 162-163

(There may be more views or larger images available for this item. Click on the thumbnail image to view.)

Found in castle. Hodges (1893) refers to it as part of large cross-head. His description, and his inaccurate but detailed drawing, preserved at Cragside, Northumberland, make clear that this stone is meant.

A (broad): Two panels not separated by a horizontal moulding are set within a deeply incised flat curving frame. (i) A short panel in which two ribbon-like features cross each other with narrower extensions which link and form triangular twists. The right side of the panel is missing; it is possible that these were two animals, but the heads as seen by Hodges are now not apparent. (ii) Set slightly to the left of the top panel are two confronted beasts. Their double-outlined bodies cross twice in a twist and curve away to the left. They have bear-like heads with squared-off muzzles, round eyes and rounded ears. Their mouths are indicated by a deep slash. Under their jaws their paws cross and disappear behind their bodies to fill in the spaces between the loops with either triangular or oval twists. The plain surface at the bottom right of the curving frame is smoothly dressed.

B (narrow): There is no sign that this face was ever carved. It is roughly cut back and nothing of its original form seems to survive.

C (broad): The shape of the face is emphasized by a curving incision and worn roll and cable mouldings.

D (narrow): This concave face is filled by a panel of very worn four-cord interlace inset in an uneven flat incised frame. Hodges' drawing shows it with a pattern E at the top, but his drawing of the interlace below is unsatisfactory. The base of the stone is broken off.

A socket-hole on faces A and D seems to be secondary.

E (top): A panel of relief ornament is set within an uneven incised frame which tapers towards the base. The panel is nearer to face D than face B. The ornament consists of two large intersecting loops with twisted terminals. Two other twists also fill the spaces within the loops. The ornament is cut off by the frame.

This piece was described by Hodges as a large cross-arm and has hitherto been accepted as such. However, it is much more convincing if the animals are seen in an upright position and the piece can then be interpreted as the arm of a chair or throne (Fig. 18). The most elaborately carved face with the animals would be extended with the pattern following the curve of the arm towards the seat. On the inner broad face, which is noticeably partly worn by use, the edge (which would partly show beside a seated figure) is also carved, as are other visible faces at the top and the front of the arm.

It is not clear how the arm would be set into the back or seat. If it were an ecclesiastical chair, then it might have been set against a wall and into a stepped base (see Monkwearmouth 15a-b). If a free-standing secular or religious seat, it may have been grooved into a back. Whole or parts of Saxon stone seats have been found at Monkwearmouth, Hexham, Beverley, Norwich and Lastingham This is the most elaborately carved of them all, and it is unfortunate that it is not securely related to a building. There is, however, a reference in Bede's Ecclesiastical History to a church dedicated to St Peter at Bamburgh, in which were preserved the relics of St Oswald (Bede 1969, III, 230). Such a seat could have been used either by a visiting bishop or secular dignitary. However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that this could be a secular seat and as such used by the kings of Northumbria and earls of Bamburgh.

The ornament of this piece contains elements which derive from the established Hiberno-Saxon tradition, and what seems to be a pre-figuring of Viking art. The two animal panels could be seen as ultimately derived from manuscripts and indeed the Durham manuscript, B.II.30, has similar compositions of paired upright animals with crossed paws on fol. 81 v. However, in the manuscript the animals are arranged in fours and they have a more elaborate background of interlace formed by ear and tongue extensions. The interlace between the Bamburgh pair is possibly formed from their tails only. Nevertheless, the bearlike heads of these beasts are found also on other animals in this manuscript. The Bamburgh beasts seem intermediate between animals from manuscripts of c. 750 and the Anglo-Viking animals of Collingham (Collingwood 1927, fig. 31).

A similar ambivalence is found in the interlace. The clever chain of twisted loops could well be seen as early in the Anglo-Viking context and related to the ring-chain, as is presumed for the single looped device on Bywell 1. However, twisted loops as elements within complex interlace occur on what must be much earlier pieces – the `reading desk' (Jarrow 22), and an impost from Hexham (no. 33). These could be as early as c. 700. It seems, therefore, as if the Bamburgh piece could best be placed within a firmly pre-Viking tradition.