Select a site alphabetically from the choices shown in the box below. Alternatively, browse sculptural examples using the Forward/Back buttons.

Chapters for this volume, along with copies of original in-text images, are available here.

Object type: Two fragments of a cross-shaft

Measurements:

a: L. 39 > 20 cm (15.4 > 7.9 in); W. 30 cm (11.8 in); D. built in

b: L. 29 cm (11.4 in); W. 19 cm (7.5 in); D. built in

Stone type: The two stones are petrologically very similar. Dolomitic Sandstone, grey-green, extremely fine crystalline with scattered mica flakes: Skerry. Upper Triassic from the Mercia Mudstone Group, a local Nottinghamshire stone

Plate numbers in printed volume: Ills. 104-7; Figs. 26-8

Corpus volume reference: Vol 12 p. 170-4

(There may be more views or larger images available for this item. Click on the thumbnail image to view.)

Stone 1a is built into the south face of the western respond of the south nave arcade, 1.85 m (6 ft) above the floor and 10 cm (4 in) from the west wall of the south aisle.

Stone 1b is built into the east face of the north respond of the tower arch, 1 m (39 in) above the floor.

Only one face of each stone is visible, and both, unusually, are irregular fragments with no other face surviving, rather than systematically cut up and recycled sections of the original monument. This may suggest that the monument was smashed rather than systematically recycled. Both decorated faces that are visible could come from the same face of the original monument and they are described and reconstructed as if that were so.

The stone type is available from local outcrops some miles to the west or south west. It seems to have been chosen for this sculpture because its even texture encourages fine decoration in very low relief.

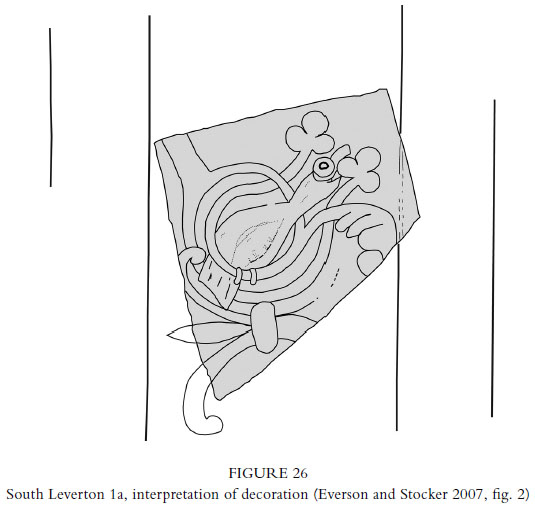

Stone 1a (Fig. 26)

A (broad): The surviving decoration seems to comprise most of the width of the vertical field of the cross-shaft. Its orientation is apparently indicated by a short length of plain border passing obliquely to the present upper edge of the stone, though it is difficult to be certain of this important detail. If it is an original feature of the stone, and not later damage, it probably represents the inside edge of the worked border moulding which we can presume ran up all four angles of the shaft. The main structure of the decoration comprises a running plant-scroll, one complete whorl of which is preserved, together with a thick stalk rising from the motif below and terminating in a three-leaved 'bud', or three-petalled 'flower', extending towards the reorientated left-hand border of the monument. The leaves or petals have tightly curled tips, which enclose an elongated triangular 'bud' between them. This flower is bound at the base by a simple rectangular fillet. Above, the pattern continues with a thick stalk, of which the surviving 'whorl' is the lowest element. Resemblance to a real vine is enhanced by two details within the whorl, which are also characteristic of this type of decoration. First, to the right-hand side as it was originally viewed, are a pair of three-lobed 'berry' bunches, and below them a more complex figure, partly missing on this stone, with apparently inscribed lines within a curving 'hood'. This looks like the remains of a curling leaf with perhaps four divisions. Within the centre of the whorl, the complex pattern of interlacing stalks is interrupted by a figure, which is unfortunately also difficult to read but seems best understood as a perching bird, with an oval body, a chisel-shaped tail and a small head, with its eye and beak extending upwards to peck at the berry bunches.

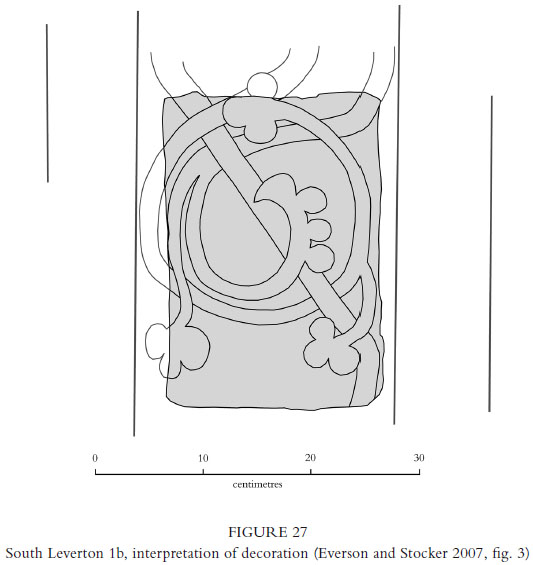

Stone 1b (Fig. 27)

A (broad): No original borders are evident on stone b; but the decoration appears to represent the lower element of the design seen on stone a. Rotated through 90 degrees from its orientation in the wall fabric so that a blank area stands to the bottom, it incorporates what might presumably be the lowest 'whorl' of foliage within the design. Like that on stone 1a, this whorl is composed of three interlaced stalks of different gauges, two of which terminate within this stone. They end, in one case, with a bifurcation and two trefoil berry bunches and, in the other, with another bifurcation, with one branch ending in a third berry bunch and a second ending near the centre of the whorl in a leaf of 'sub-acanthus' type with four lobes, the uppermost of which has a curled tip. This leaf might be of the same genus as that to the left of the bird on stone 1a, while the trefoil berry bunches are identical to those on stone 1a. The whorl on stone 1b is developed around a broad stalk, which is rooted in the blank panel beneath and which evidently zig-zags from side to side, interlaced with the whorl's stalks, but independent of them. This broader stalk type reappears on stone 1a, where (for example) it seems to terminate in the tripartite 'bud'.

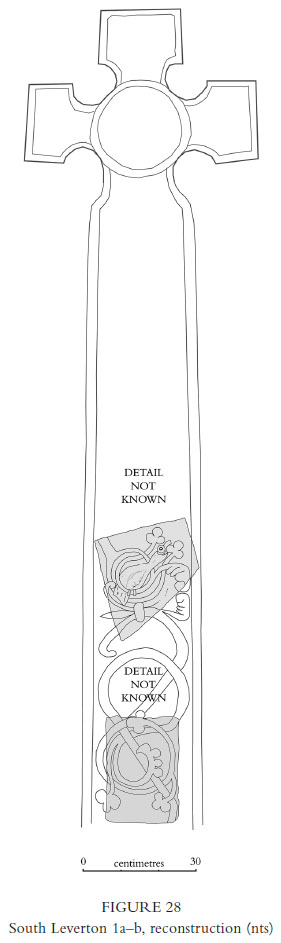

These two stones are of precisely the same stone type and are decorated in the same low-relief style. It is clear that they are fragments from the same original monument, and together represent a major cross-shaft decorated on one face with a conventionalised plant-scroll inhabited by at least one bird and no doubt topped with a cross (Fig. 28). The symbolic meaning of the vine itself as a reference to the Cross, the Tree of Life and to the Eucharist are familiar enough (most recently discussed by Hawkes 2002, 90–3).

Inhabited plant-scrolls such as we see at South Leverton are frequently found on sculpted crosses of the eighth and ninth centuries, and debased versions continued to be carved well into the tenth century, following the Viking incursions. Typologically, the tightly packed whorls of the South Leverton stones, with very little of the background left uncarved, is a feature normally placed towards the end of this sequence, during the ninth and tenth centuries. At the latter end of this date range, however, the scrollwork itself often becomes much more repetitive and loses the distinctions between differing thicknesses of tendril, berries and flowers that is deployed on the South Leverton piece. Furthermore, it is comparatively rare for such putatively late plant-scrolls to be inhabited, especially with birds apparently eating the berries on the vine. This distinctive detail can in fact be reckoned an earlier feature, on the basis of cynosures like those at Bewcastle, Ruthwell, Jedburgh and Otley, all of which belong to the later seventh or early eighth centuries (Cramp 1984; Bailey and Cramp 1988; Coatsworth 2008). Of these classic monuments, perhaps the most similar to the South Leverton shaft are those at Closeburn (Dumfriesshire), a shaft which was dated by Collingwood to the early ninth century rather than the eighth (1927, 54–5, fig. 68), or the more recently discovered fragments from shaft 30/31 at St Oswald's, Gloucester, dated to the mid or later eighth century in its original publication (Bryant 1999, 154–5) and to the last quarter of the eighth century in its recent reassessment (Bryant with Hare 2012, 207–8, ills. 265–73). The positioning, stance and overall proportions of the bird that we discern at South Leverton are particularly reminiscent of the bird within the lower volute of face B of the Gloucester cross-shaft (ibid., ill. 273), though its degraded detailing does not allow us to identify it decisively with the 'thrush type' familiar from top-class Northumbrian monuments.

Closer, in both location and stylistic details, is the north shaft at Sandbach (Cheshire), where the scroll inhabited by birds and quadrupeds on stones IV and V has tripartite leaves similar in general type to those at South Leverton and at least one bunch with three berries (Hawkes 2002, especially 85–93; Bailey 2010, ills. 249, 257, 261). Furthermore, there are significant similarities between the Sandbach north cross and a section from a similar monument now cemented into the south porch at Bakewell church (Derbyshire), only twenty miles to the south west of South Leverton (Hawkes 2002, fig. 2.31). Hawkes identifies specifically Mercian design details on both the Sandbach and the Bakewell monuments (2001, 231–5) and it would seem likely, therefore, that the South Leverton monument should be viewed as arising from the same specifically Mercian context. Indeed there are a number of cross-shafts with plant-scroll decoration in Derbyshire which offer points of similarity with the new pieces. Although not inhabited in the same way, the plant-scroll on the major shaft in Bakewell churchyard has tightly coiled whorls with tripartite 'buds' between each whorl and leaves with curled tips, similar to those seen at Leverton (Routh 1937, pl. I, A and C), whilst another fragment in the porch at Bakewell has a bunch of three berries at the end of a long tendril, like those at South Leverton (ibid., pl. III, B; see Ill. 190).

A fragment from a similar plant-scroll at Scalford (Leicestershire) also has two thicknesses of tendril and tripartite flowers with tightly curled buds of very similar type to Leverton (Parsons 1996, 17, fig. 4a). Although not such a close parallel as Scalford and not a shaft, the famous broad frieze at Breedon-on-the- Hill (also Leicestershire) employs inhabited plant-scroll of this type, with tendrils of two thicknesses and generically similar tripartite buds (Cramp 1977, fig. 50; Jewell 1986). The Breedon birds have similar chisel-like tails to that at South Leverton; but they have one wing outstretched, and just possibly such a raised wing might underlie the badly disturbed surface area above and behind the Leverton bird. Also within this north Midlands region, the fragment from a major shaft that was re-worked as a font at Wilne (Derbyshire) is decorated with a plant-scroll containing bird-like animals. The leaf forms are not closely similar to those at Leverton, but the scrolls on the two monuments share similar heavy bindings on their thicker stalks (Browne 1891–2). Although none affords a closely similar parallel to it, these examples do establish that different types of plant-scroll, of the general type seen at South Leverton, were a conventional sculptural decoration in this part of north-eastern Mercia in and before the ninth century, probably drawing their inspiration from the finest stone monuments of Northumbria. Furthermore, with the exception of the frieze from Breedon, this decoration was used on standing cross-shafts, of the type we believe is represented at South Leverton.

Some caution is required, however, in suggesting a pre-Viking date for the newly discovered Leverton shaft. Fragment no. 16 at Billingham (co. Durham), possibly from a shaft, contains a tripartite bud of similar form to that on stone 1a at Leverton (Cramp 1984, 52–3, pl. 17.88). Rosemary Cramp places that piece in the eleventh century, and closely similar leaf forms occur in manuscripts of the tenth century, as in the marginal decoration of Corpus Christi College MS 183 f. 1v (Temple 1976, 37–8). This leaf type owes its origins to pre-Viking styles, however, such as the superb monument at Cropthorne (Worcestershire), where tripartite buds, trefoil leaf forms and birds with chisel-shaped tails survive in excellent condition on a cross-head usually dated to the early ninth century (Webster and Backhouse 1991, 244–5, cat. 209; Bryant with Hare 2012, 353–6, ills. 621, 625). It provides an example of the use of all these details at a similar date to that we propose for South Leverton 1. For, overall, Leverton exhibits a clear understanding of plant-scroll, and in deploying birds integrated with the scroll and reaching to peck at berry bunches it looks towards an early iconographic tradition. It sits comfortably in the pre-Viking period and represents an extension of the distribution of the types of Mercian monument found at Sandbach, Scalford and Bakewell, both somewhat further to the north east and across county boundaries into Nottinghamshire. The scroll is heavily stylized, which perhaps suggests a ninth-century rather than earlier date; and even if, with its degraded surfaces, we have over-interpreted the leaf forms, the example of the north cross at Sandbach, with its defoliated scroll and pellets instead (Bailey 2010, ill. 261), demonstrates the range of depiction current within the region.

In publishing an earlier account of this monument as a major pre-Viking cross-shaft and rare new discovery in the county, we deployed historical, architectural and topographical arguments to investigate its likely — though hitherto unsuspected — context (Everson and Stocker 2007, 41–8). This study identified a major enclosure at the heart of the morphology of the medieval and later settlement of South Leverton, within which the church of All Saints sits awkwardly and peripherally. Various indicators pointed to the early importance of Leverton — latterly subdivided into North and South — within the early region of Hatfield or 'The Clays'. We proposed that this combination of insights could be taken to identify an early Christian institution at South Leverton, within whose focal enclosure there were multiple features that included at least this major cross, the church of All Saints and a well. Our subsequent assessment of South Leverton 2 as the remnant of a pre-Viking rood (see below) further elaborates and enhances the distinctive, characteristic features of that early institution. It was probably a 'monastery' in the terms envisaged by Eric Cambridge (1984), though precisely what that term might signify at this early date is a matter of lively contemporary debate (Blair 2005). This historical context is explored further above (pp. 24, 74–5).