Select a site alphabetically from the choices shown in the box below. Alternatively, browse sculptural examples using the Forward/Back buttons.

Chapters for this volume, along with copies of original in-text images, are available here.

Object type: Part of grave-cover [1]

Measurements: L. 80 cm (31.5 in); W. 35 < 41 cm (13.8 < 16.1 in); D. 33 cm (13 in)

Stone type: Limestone, pale yellow-buff, medium to coarse, ooidal and sparsely bioclastic, well cemented. Middle Jurassic, Bajocian, Upper Lincolnshire Limestone Formation, Ancaster Stone

Plate numbers in printed volume: Ills. 94-9; Fig.25

Corpus volume reference: Vol 12 p. 165-8

(There may be more views or larger images available for this item. Click on the thumbnail image to view.)

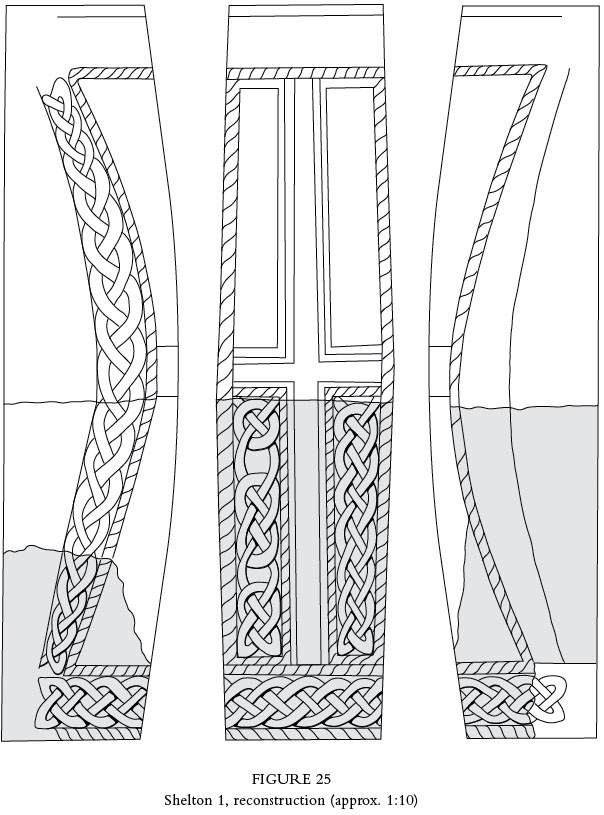

This stone represents approximately one half of a grave-cover which belongs generically with the 'hogback' group. Lang (1984, 101, type VIII, fig. 9) described the form of this monument when he defined the 'wheel rim' type; so called because of the large semicircular end piece. This example is quite sharply tapered in plan, or (perhaps more probably) it was bow-sided, curving outwards towards the centre. In addition to this distinctive plan form, the geometry of its surfaces is also very complex. The 'wheel rims' at either end were connected with each other by a bold broad fillet down the centre of the 'lid', and this formed the head and foot of the major cross with which we presume the monument was decorated. It is also probable, though un-provable at Shelton, that this bold fillet bowed upwards as well, giving the monument the characteristic 'hogback' profile, seen in Shelton 2. To either side of the head and foot of the bold cross-shape, the lid was not carved in a single plane, but also rose from the ends, against the 'wheel rim', towards the central cross bar (Fig. 25).

A (top): The 'wheel rim', which curves down on both sides to merge imperceptibly with faces B and D, is outlined with runs of cable moulding. Inside the panel thus created is a continuous run of four-strand plait formed by interlace strands without the enhancement of an incised line. This plait terminates in two box points at its junction with the longitudinal interlace decorating face B, rather than connecting with it. These neatly carved, cable-moulded borders originally ran continuously both along the arrises that distinguished the lid from the 'side' and also along either side of the broad fillet down the ridge of the monument that formed the head and foot of the presumed central cross. It also forms the remainder of the frame around the sunken panels of interlace that flank the presumed main cross along the ridge. The sunken panels so defined occupy the two surviving of the original four interstices of the cross, and were presumably mirrored in the two lost panels. Within each are two runs of interlace carving in low relief, again without the enhancement of an incised medial line. The panel adjoining face D is a continuous run of four-strand plait, terminating against the 'wheel rim' with two box points. That adjoining face B also terminates in two box points, and is also a four-strand plait, but the interlace resolves itself into a number of discrete units, one of which is of motif type iv (Everson and Stocker 1999, fig. 10) and at least one of the others was a figure-of-eight or 'Stafford knot' (simple pattern F).

B (long): The interlace decoration on the 'wheel rim' merges imperceptibly with face B but does not link up with it. Instead the decorated longitudinal panel is narrower and bows upwards, possibly mimicking the original profile of the monument's ridge. It is defined along its upper border by the cable moulding already mentioned, but there is no moulding dividing it from the large plinth, which also rises within the stone to give the monument a 'hogback' profile. Within the panel the unornamented interlace strands, carved in low relief, form a continuous run of three-strand plait and terminate against the plait decorating the 'wheel rim' with a free end. Towards the opposite end of the surviving stone, about half of the surface of face B has been planed away when the stone was reused, as the original 'bow-sided' stone was reduced to a regular rectangle for re-cycling as building material.

C (end): This side of the 'wheel rim' appears to represent the original undecorated surface of the stone. It retains a neat diagonal 'striated' tooling using very broad drafts (Stocker 1999, 344–5).

D (long): The outer end carries the termination of the plait-work decorating the 'wheel rim', in an area where it meets the remaining surface which has been completely planed away during the stone's re-cycling as building material.

E (end): This is entirely the product of the monument being halved across the centre for reuse as building material.

F (bottom): Like face C, this appears to represent the original undecorated surface of the stone. It retains a neat diagonal 'striated' tooling using very broad drafts (ibid.).

Shelton 1 was identified in our Lincolnshire study as the best preserved and most complete of a distinct East Midlands sub-type of hogback monument. Developing Lang's analysis, we called the five known examples of this type 'Trent Valley' hogbacks (Everson and Stocker 1999, 35–6; this volume, pp. 51–3). Of the remaining four, the pair from Lythe in north Yorkshire (Lang 2001, 164–5, ills. 569–71, 577–9) have relatively little in common with those from the East Midlands and it is only the unusual geometry that associates them with the group. That leaves two close parallels for Shelton 1: one at Cranwell in Lincolnshire (Everson and Stocker 1999, 136–8, ills. 109–20 and fig. 25; here Ill. 189) and the other from St Alkmund's church, Derby, now in Derby Museum. This latter stone, catalogued by Routh (1937, 24–5, pl. XII), by Radford (1976, 53–4, no. 9, pl. 10a–b) and by Lang (1984, 128 and plates), has the same surviving ridge profile that may be conjectured for Shelton 1 (above). Of the two comparanda, though, Shelton has much more in common in detail with Cranwell 2. Both are from the same quarries, for example, being of fine oolite from the Ancaster region, and both follow an apparently very similar pattern of decoration. The principal difference between the two monuments seems to be that Shelton 1 was considerably smaller when complete than Cranwell, and may not have been quite so stylishly decorated. All the interlace at Cranwell is enlivened with an incised medial line, for example, and negotiates changes between three and four-strand plait through careful design layout. At Shelton, the strands are less carefully rounded and do not have the decorative elaboration. Also, rather than transform four-strand into three-strand plait, the two interlace forms on face B simply butt against each other. Even so, the two monuments were clearly closely similar and must be close in date as well.

By contrast, the example from St Alkmund's, Derby is of a different, Derbyshire stone type and the interlace takes an entirely different form. The 'wheel rim' here is reduced in prominence and retains a very stylized 'bear' looking along the ridge-rib. The strands at St Alkmund's are also much less symmetrical than those at either Cranwell or Shelton 1, and the origin of the interlace form in writhing animals (such as those enmeshed in interlace at Hickling (p. 115), and on other shafts from St Alkmund's) is made very clear by the thickening of certain strands to form the bodies of 'ribbon-beasts' and the carving of distinctive faces on the 'free ends' of the strands. Cranwell 2 also has distinctive terminals decorating the 'free ends', but there they are 'arrowheads' rather than zoomorphic details. Such terminal decoration is not found on the single 'free end' at Shelton.

If we were to try and place these three stones in chronological relationship with each other on this basis, it might make sense to place them in this order — Derby, Cranwell, Shelton — as this expresses a typological development from a form of interlace with many vestiges of the 'ribbon-beast' through to an interlace form that is entirely abstract. More substantially, a detailed case has been made (based to a large extent on similarities and differences with the St Alkmund's stone) that the Cranwell monument should be dated to the 'mid tenth century, perhaps second quarter', and that it forms a pattern for the mid-Kesteven covers mass-produced in the Ancaster quarry belt from the mid tenth through the early eleventh century (Everson and Stocker 1999, 35– 6, 136–9; Stocker and Everson 2001). This line of argument would lead to a date around 950 for the example from Shelton.