Select a site alphabetically from the choices shown in the box below. Alternatively, browse sculptural examples using the Forward/Back buttons.

Chapters for this volume, along with copies of original in-text images, are available here.

Object type: Architectural feature (sundial) [1] [2]

Measurements: H. 53 cm (20.75 in); W. 235 cm (92.5 in); D. Built in

Stone type: Fine-grained, white (10YR 8/2) sandstone, with iron nodules; see no. 1; from North Yorkshire Moors

Plate numbers in printed volume: 568-573

Corpus volume reference: Vol 3 p. 163-166

(There may be more views or larger images available for this item. Click on the thumbnail image to view.)

The stone is divided into three panels. The central one contains the sundial and it is flanked on either side by inscription panels. Within a broad, flat outer moulding framing the whole stone, there is a second, narrow moulding of similar profile which runs right across the top. The inscription panels are further defined by pairs of broad, flat mouldings, only the outer of which is carried across the tops.

The sundial in the central panel consists of a raised pendant semicircle with a double arc. There are nine symmetrically arranged radial lines from the hole for the gnomon. Each alternate line has a small cross-terminal, the others having none, except for the second from the left, which has a saltire. The only other decorative features are the crosses at the end of inscription (a) and the beginning of inscription (b), which have slightly splayed arms approximating to type B6, defined by a single incised line; each contains a simple incised cross within.

Inscriptions Old English inscriptions in Latin lettering appear in all three panels.

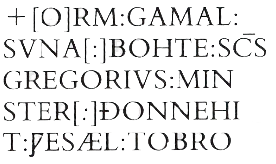

(a) The lines of the main text are disposed symmetrically between the two sunken panels on either side of the sundial, although the second half of the inscription is more crowded than the first. The distance between the deeply incised horizontal guide-lines varies slightly in the range of 7–8 cm. The letters are between 4.5 and 6.5 cm high. The text reads:

(left):

(right):

This may be read as: + ORM : GAMAL : SVNA : BOHTE : S(AN)C(TV)S GREGORIVS : MINSTER : ÐONNE HIT : ǷES ÆL : TOBROCAN : 7 TOFALAN : 7 HE HIT : LET : MACAN : NEǷAN : FROM GRVNDE : CHR(IST)E (or CR(IST)E : 7 S(AN)C(TV)S GREGORIVS : IN : EADǷARD : DAGVM : C(I)NG 7 (I)N : TOSTI : DAGVM : EORL +

(Translation): 'Orm the son of Gamal bought St Gregory's minster when it was utterly ruined and collapsed and he had it rebuilt from the foundations (in honour of) Christ and St Gregory in the days of King Edward and in the days of Earl Tosti.'

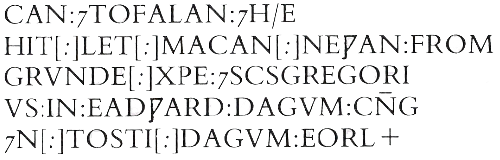

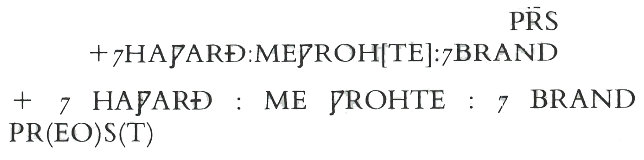

(b) A second text, on the same scale as a, with letters of 5.5–6 cm high, is set at the bottom of the central panel under the dial. It runs under an incised horizontal, but the last word overflows into the space above. It was perhaps thought of as a continuation of inscription a, as it is preceded by the same kind of emphasized incised cross as appears at the end of that text. It reads:

PRS may alternatively be expanded to the Latin PR(E)S(BYTER) (Translation): 'And Hawarð made me and Brand the priest.'

(c) The third text is inscribed in smaller letters around the dial itself, and is in two sections which, however, are probably to be taken together. The letters running across the top of the dial are about 3 cm high and those running along its circumference measure about 2 cm. It reads:

(top of dial):

+ ÞISIS[:]D[ÆG]ES:SOLMERCA+

(circumference of dial):

ÆTILCVM[:]T[IDE]+

+ ÞIS IS : DÆGES : SOLMERCA + ÆT ILCVM TIDE +

(Translation): 'This is the day's sun-marker at every hour' or 'This is the mark of the sun for each (canonical) hour' (Page 1971, 179–80).

Some thought was evidently given to the design of the stone and its inscriptions. The main inscribed panels are arranged symmetrically and deeply incised horizontal lines separate the lines of text. There is an apparently otiose incised line above the top line in the left panel but not on the right. This distinction may have been intended to indicate that the text carries on without a break from one panel to the next. The detailed laying-out of the inscriptions is, however, clumsy. In inscription (a), the left-hand panel is generously spaced, whilst that on the right becomes highly compressed from the end of the first line (Higgitt 1979, 353–4). In inscription (b), the PRS of the maker formula overflows from the line below the dial: probably a miscalculation rather than an afterthought. The inscription on the dial, (c), is also unbalanced in its arrangement. It starts clear of the semicircular framing lines on the left but crosses them on the right.

Crosses introduce the three sections of text and appear at the end of the main text, (a), and at the end of the two sections of the dial inscription, (c). The more elaborate crosses at the end of the right panel of inscription a and at the beginning of the maker formula, (b), may have been designed, like signes de renvoi in manuscripts, to show that the text of (a) carried on from the right panel back to the bottom of the central panel, (b).

The letters are boldly cut and well preserved. The paint used to pick them out is modern but it is very likely that early medieval inscriptions were often painted in this way (Higgitt 1986, 131–2, 138–9, 143). The modern paint, which is now rather worn, seems to have followed the carving with some care.

Slightly clumsy serif-less capitals are used. A has a bar over the top. The bar over the first A in TOFALAN is interrupted by a gap in the middle. The cross-bar of A is either angular or leans down to the right. C and E are normally square, with one example each of the rounded version of the letters. M has vertical outer limbs. N is Classical in form, except in C{*bar over N*}NG and BRAND, which have the form in which the diagonal touches the verticals short of their ends. The diagonal of the first N in line 4 of the right-hand panel is slightly sinuous. O is normally lozenge-shaped, with only one example of the round letter. R is open. S is a comparatively unusual variant of angular S in which the middle stroke is vertical. Three Old English graphs appear: capital eth, thorn, and wynn. The Tironian sign consistently stands for and or ond. Single mid-line points seem to have followed most words except the conjunction and. The use of a pair of points after XPE rather than the single point used elsewhere was perhaps intended to give a special emphasis to Christ's name. (LET in line 3 of the right-hand panel may also have been followed by a pair of points, but the stone is too damaged to be certain.) The nomina sacra for Christ's name and for sanctus are employed. In the last line of the right-hand panel N stands for IN. If I was not omitted in error, then it is possible that N was regarded as a monogram of IN (Okasha 1971, 88, 157). The following abbreviation is also used on the cross-head from St Mary Bishophill Junior in York (no. 5; Ill. 234).

There it stands for presbyter, as it may do at Kirkdale, although preost is perhaps more likely in an Old English inscription (Okasha 1971, 157. See also p.86).

==J.Higgitt

This is the most remarkable and complete pre-Conquest sundial surviving, not least because its inscription names its carver, the patron saint, the priest, the landholder, the king, and the earl. Hence it was made during or shortly after the period when Tostig was Earl of Northumberland, that is, 1055–65. The decorative carving is minimal, unfortunately, though the rectangular form, with the semicircular dial placed centrally, is similar to Great Edstone 1. Since the church has undergone several repairs over the centuries, the dial perhaps being reset in rebuilt walls, it does not necessarily place a chronological seal on those other fragments contained in the church fabric; its use as a means of dating the fabric certainly needs to be approached with caution (Morris 1988, 196).

Inscriptions The principal text, a, records and displays the same sort of information as does the inscription at St Mary Castlegate in York (no. 7; Ill. 312). The text opens with the name of the patron of the rebuilding and owner of the church (called a minster as at York). It also records the dedication to Christ and and St Gregory, although there is no direct reference to an ecclesiastical ceremony of dedication, such as is implied by the 'consecratio' of Castlegate 7. The rebuilding is then dated by naming the men who were then the king of England and the earl of Northumbria. Beneath the dial a brief text, b, personifies the monument in a common Anglo-Saxon maker formula (X me wrohte). Hawarth was probably the craftsman; Brand, the priest, was perhaps responsible for the drafting and laying-out of the text, and perhaps too for the design of the dial (Higgitt 1979, 354). The text on the dial, (c), refers, redundantly but proudly, to the working of the sundial.

The language of the inscriptions, though clearly English, deviates a good deal from the classical form of Old English. It shows such late features as the weakening of unstressed vowels (suna, tobrocan, tofalan), loss of distinction of endings (macan, the genitives Gamal, Eadward, Tosti, c(i)ng, eorl), confusion of grammatical gender (newan minster, ilcum tide). These could be the effect of a strong Norse admixture in the local population, as evidenced by Norse names in the inscription, Orm, Gamal, Hawar ð, Brand, but it is not necessary to assume so. [4]

The word solmerca can either be taken as a hybrid Old Norse and Old English word meaning 'something which marks (the position of) the sun', or an Old Norse loanword meaning 'the mark of the sun' (Page 1971, 180).

The slightly rough lettering, with its preference for angular forms, and the use of the vernacular, contrast interestingly with the cosmopolitan elegance of the well-spaced lettering on the contemporary Latin inscription at Deerhurst in Gloucestershire (c. 1056 or a little later), which shows a preference for rounded forms and occasionally inserts smaller letters inside larger ones (Okasha 1971, pl. 28). Continental (ultimately Carolingian) influence is clear at Deerhurst, deriving either through English manuscripts of the Reform period or through direct contacts with eleventh-century epigraphy, perhaps in France. It may be relevant that Deerhurst was granted to the abbey of St-Denis, near Paris, a year or so after the dedication commemorated in the inscription (Knowles and Hadcock 1971, 64). (See further Chap. 12, pp. 46–47.)

==J.Higgitt

1. The following are general references to the Kirkdale stones: Allen and Browne 1885, 353; Norman 1961, 267; McDonnell 1963, 56; Lang 1989, 5.

2. The sections on the inscriptions are by J. Higgitt.

3. I am grateful to Professor R. I. Page for drawing my attention to this reference.

4. The preceding paragraph was supplied by Professor R. I. Page.