Select a site alphabetically from the choices shown in the box below. Alternatively, browse sculptural examples using the Forward/Back buttons.

Chapters for this volume, along with copies of original in-text images, are available here.

Object type: Part of cross-arm [1]

Measurements: H. 10.3 cm (4.1 in); W. 11.3 > 9.75 cm (4.8 > 3.8 in); D. 5 cm (2 in)

Stone type: Fresh, unweathered sandstone, pale yellowish brown, fine to medium grained, quartzose, quartz-cemented, slightly micaceous. Low angle, fine cross-lamination evident. Upper Carboniferous, local Middle Pennine Coal Measures Group. [G.L.]

Plate numbers in printed volume: Ills. 230-4

Corpus volume reference: Vol 8 p. 142-5

(There may be more views or larger images available for this item. Click on the thumbnail image to view.)

Part of a cross-arm, possibly from the double curved arm of a cross-head of type D9/10. The carving is shallow and in a flatter style than in Dewsbury 1–5, 8 and 9 discussed above. The faces are edged with a cable moulding in which each twist of the cable is incised centrally with a line running in the same direction, which Collingwood called a 'reel' pattern. Note that the twist is Z-plied on the left of the main faces and S-plied on the right.

A (broad): This face is filled by an inscription set out without framing lines horizontal to the face. This is therefore part of the upper or lower arm of the cross.

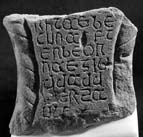

Inscription One of the two broad faces carries seven lines of an incomplete inscription (Ill. 230; Okasha 1971, no. 30). A fragment of the bottom of a curving letter above the B in the first surviving line shows that at least one line has been lost above what remains. The lettering is incised and unusually small (1 cm in height). It reads:

| [R]HTAEBE CUNA[E]FT ERBE[O]R NAE GIB[I] DDADD [AE]R [:] SA V[LE] |

Divided into words this gives: — RHTAE BECUN AEFTER BEORNAE GIBIDDAD DAER : SAVLE. The stone is broken away above the first surviving line, which begins in mid word. The last line, however, appears to be the end of the inscription or at least of this section of text, since there is empty space where more letters might have followed. The line-breaks do not respect word- or syllable-division. A slight gap seems to have been left deliberately after BEORNAE to mark the end of one sentence and the beginning of another. What appears to be a mid-line point, although it could be due to damage, separates GIBIDDAD and SAVLE. The text can probably be translated '[X set up this] monument in memory of –berht, his son; pray for his soul'. Two details here are open to alternative interpretation, however, and are discussed below.

The inscription belongs to a widespread group of Northumbrian vernacular memorial-texts, some of them (including this one) in loose alliterative verse (see Chap. VIII, pp. 79–84). The parallels suggest that – RHTAE is likely to represent the end of a personal name, inflected in the dative case; the common masculine name-element –beorht or –berht comes to mind (cf. Thornhill 1, p. 256). A conceivable alternative, though without close parallel, would be a verbal form like worhtae 'made', giving perhaps 'X made this monument in memory of BEORNAE ...'.

The second point for comment is the identification of BEORNAE. Formally this could be a personal name: Beorn is a well-attested monothematic name in Old English (Redin 1919, 4). However, to judge again by the parallels, BEORNAE here is more likely to indicate the relationship between commemorator and commemorated. Falstone has AEFTAER EOMAE 'in memory of [his] uncle' (Okasha 1971, 71–2; Cramp 1984, 172), Yarm has AEFTER HIS BREODER 'in memory of his brother' (Okasha 1971, 130; Lang 2001, 274), and Great Urswick has 'æfter his bæurnæ', which may be closely analogous to the present text and uses a possessive which in that case precludes a personal name (Page 1999, 141, 150–1; Bailey and Cramp 1988, 148–9).

At both Great Urswick and Dewsbury there is then uncertainty as to whether the forms in question represent Old English bearn 'son' or Old English beorn 'man, warrior, noble'. Superficially, Dewsbury's BEORNAE naturally suggests the latter. However, early and, especially, northern varieties of Old English frequently confuse standard ea and eo (Campbell 1959, §§276, 278). On formal grounds, therefore, there is no secure way of telling which word is intended here, and different arguments must be sought if one reading is to be preferred over the other. There may be reason to doubt the appropriateness of beorn. This has been translated 'lord' or 'chief, prince', suggesting that the inscription could be a memorial set up by a retainer to his social superior (Okasha 1971, 66; cf. Page 1999, 141). However, the Dictionary of Old English (Amos et al. 1991, B 1.3, 944–6), in glossing the term as 'man, noble, hero, warrior', cites little evidence to suggest that 'noble' is more than a vague heroic tag; the main association is clearly with martial prowess, not with social rank.[2] Nowhere in the literary texts is beorn qualified by a possessive — unlike, for example, dryhten, hlaford and þegn — and it is not a term for social relationship in documentary sources. Possibly local usage in the West Riding was idiosyncratic, possibly the verse form of the inscription gave licence to imprecise diction: it is certainly not possible to rule out beorn in some sense. However, on balance, when the clearest parallels involve 'brother' and 'uncle', it seems likely that the intended word here is Old English bearn 'son'.[3]

The lettering is not entirely regular but it is set out neatly between lightly incised guide-lines. The letter-forms are Insular half-uncials. A takes its usual Insular half-uncial 'oc' form. Minuscule D is used for both D and in place of þ/Ð. F lacks the usual serif at the top of the vertical. R is uncial in form or, in the case of the second R in the third line, an angular variation on that letter. S in the sixth line is reversed, presumably in error. The letter transcribed above as U resembles the 'uncial' form of N employed in Insular half-uncial but was probably intended as an angular treatment of half-uncial U. The tops and bottoms of strokes are often finished off with wedge-like serifs typical of this script.

B and D (narrow): Within the cabled borders of this very small slim monument is an angular, but very regular ornament which could be read as either a simple angular twist or as a step pattern type 2. The surface of the strand is flat, the cutting delicate and precise.

C (broad): The strand is again flat and rather angular. One volute and part of another of regular spiral scroll are present. The scroll of the complete volute starts from a double binding and ends in a large round berry, or perhaps a flattened berry bunch. All spaces on the outside of the scroll are filled with dependent serrated leaves, the serrations expressed by finely incised lines.

This fragment of a very small cross-head shares an unusual cable moulding with the cross-head Dewsbury 12 (Ills. 225–7). Although in a flatter style than Dewsbury 1–5, 8 and 9, this is a delicate carving of a very fine quality. The ambiguous twist at the sides can be read as a precursor to the side-filling step patterns of the Anglo -Scandinavian period. The plant scroll on face C has features which relate it to the tangled medallion scroll on Dewsbury 4 (Ill. 201) and to the early period at Otley and other major Yorkshire sculptures of the pre-Viking period (see Chap. V, pp. 52 and 53). Collingwood (1915a, 167–8) placed Dewsbury 10 at the very end of the pre-Viking period, but this is not borne out by a study of the parallels to the ornament or the lettering. His reasons included the slimness of the head, which he thought approached the slab-like proportions more often found in the Viking period. However, this piece has to be seen as a miniaturisation of the great cross-heads, as his drawings demonstrate. The inscription is enigmatic but if it is a memorial to a child, its delicacy and small scale seem rather touching.

Inscription The group of Old English memorial texts with which Dewsbury 10 belongs is discussed in Chapter VIII (pp. 79–84). The inscription recorded the name of the deceased and probably also that of the commissioner of the monument, and it concluded by asking those addressed to pray for the soul of the deceased. Similar requests in Old English and Latin for prayers are known on a number of other Northumbrian crosses and cross fragments, at Lancaster, Urswick, Thornhill and Whitby, and probably also at Alnmouth, Bewcastle, Hackness and Norham (Okasha 1971, nos. 2, 42, 67, 68, 96; Page 1999, 141–3, 144–5, 150–3; Lang 2001, 302–3, ills. 1201, 1204). They are also found on memorial stones of other forms at Billingham, Falstone, Hartlepool and York (Okasha 1971, nos. 9, 39, 46–7, 150, 152).

Dewsbury 10 can be compared to a number of other pre-Viking crosses displaying memorial or probably memorial inscriptions on their heads. The monastic site at Whitby has produced seven or perhaps eight examples and there are perhaps two from Carlisle and one each from Lancaster and York (Okasha 1971, nos. 23, ?24, 68, ?123, 124–7, 130–1, 148; Lang 2001, 241–9, 302–3, ills. 1201, 1204).

The small-scale lettering and the carefully ruled layout is reminiscent of manuscript display script in scale and formality. In inscriptions on stone the best parallel for its size is the finely executed lettering on the cross-head from St Mary Bishophill Junior in York (Okasha 1971, 132, pl. 148; Lang 1991, 45, 86, ill. 234). The York lettering was perhaps designed by a scribe familiar with manuscript display script. That on Dewsbury 10 is less fluent, and the serif-less F, the reversed S and the apparent use of the 'uncial' form of N for U do not suggest a very expert scribe.

The lettering on the cross-arm fragment from Whitby, no. 64 (Lang 2001, 302–3, ills. 1201, 1204) is similar in scale but its capitals lack the control of the inscriptions at Dewsbury and York.

The letter forms derive from those of Insular half-uncial book-script, which flourished in Northumbria from some time in the seventh century until around the middle of the ninth century. The formality of layout and execution suggest that the designer was familiar with calligraphic book-script, but details such as the reversed S betray a lack of scribal expertise. The precision aspired to in the script reflects that of 'Phase II' of Insular half-uncial, which would imply a dating in the eighth or first half of the ninth century (Brown, M. 1990, 48–55).

[1] The following are general references to the Dewsbury stones: Hunter 1834, 149–68; Nichols 1836, 39; Haigh 1857, 155n; Hübner 1876, 63, no. 173; Browne 1885–6, 128; Allen 1889, 129, 213, 217–18, 220, 222; Allen 1890, 293; Fowler 1903, 128; MacMichael 1906, 360–1; Morris 1911, 46, 174–5; Lethaby 1913, 158–9; Collingwood 1915b, 334; Glynne 1917a, 191; Collingwood 1923, 7; Collingwood 1927, 6–7, 33, 74, 109, 116, fig. 13(6); Collingwood 1929, 17, 22, 24, 28–9, 30, 33, fig. on 28; Collingwood 1932, 51, 53; Elgee and Elgee 1933, 196, fig. 36; Mee 1941, 119; Pevsner 1959, 20, 179; Cramp 1978a, 9; Faull 1981, 218; Ryder 1991, 20; Ryder 1993, 18, 149; Sidebottom 1994, 87–8, 156; Page 1995, 298; Lang and Wrathmell 1997, 375; Hadley 2000a, 248; Butler 2006, 93.

[2] The term is found only in verse (c. 130 times), though the alliterative nature of the inscriptions may be relevant here.

[3] It is possible to argue also that 'bæurnæ' on Great Urswick is formally more likely to represent bearn than beorn. (The four paragraphs on the Old English text are by David Parsons.)